GEAR

EditorialPosted August 2018

iPhone X and the state of smartphone cameras

↓

We’re later than usual when stopping for dinner, starving by now. It’s still an hour and a half before arriving at our country house, but at least we’re on our way.

GEAR

Getting a new smartphone becomes less exciting every time. Updates are iterative by now, changes to the experience subtle. Still upgrading to the iPhone X felt a little more interesting.

The X introduces fundamental shifts in interaction as well as numerous new features. Things that have significant impact in my day job – my main motivation for switching.

For the context of this site though, the most interesting thing is of course the camera system. Beyond the expected and iterative improvements to output quality the camera system in the X also brings a few new features to the table that feel interesting to touch on. These features are not unique to the iPhone X, but instead clearly illustrates the current state of photography and quite probably a great deal about its future too.

Things I wanted to dig into a little more deeply and experience fully to see how much of it is simple hype and how much it actually impacts the use of a smartphone as a camera.

So for the past few months I’ve tried a bit of an experiment – to treat my smartphone like a proper camera. I’ve aimed to get at least one image I’m happy with each day, forcing me to shoot in a more considered fashion. This has been an interesting experience, making me reevaluate a few things. I’ll get back to all that – first a bit on the state of smartphone cameras and why now is a particularly interesting time.

I rush a bit to not miss the next train. As I come out of the path through the woods something catches my eye. It’s odd how nice that looks, I think to myself. I pull up the shiny slate from my pocket and it instantly lights up. I hold it up in front of me and in seconds I’ve captured the scene. The slate goes back in my pocket as I head down the stairs to the subway.

Recent sensors have seen improvements in both resolution and dynamic range. Lenses have become brighter and sharper. Autofocus is a given these days and image stabilization is becoming increasingly common.

While a rundown of specs isn’t interesting in its own right the practical implications are. Improved lenses with autofocus means sharper images overall. Increased dynamic range makes images more flexible and look more natural. Image stabilization means better results in low light.

While these changes are iterative a decade worth of year over year improvements means we’re now at a reasonably impressive place in terms of performance with the current batch of smartphones. The output isn’t going to rival higher end dedicated cameras quite yet, but it’s certainly past sufficient for a lot of uses.

Still these mostly subtle updates doesn’t change that the smartphone has been lacking flexibility. Up until recently they’ve been offering just a single perspective and a very specific look of the output, but even that’s not true anymore.

The wind is unseasonably warm in the evenings. We play for a bit before it’s time to head home. Summer came early this year.

Computational photography

Getting the X the biggest change from my previous phone was the addition of the dual camera system, inherited from the Plus series iPhones.

At its most basic this two camera setup offers two different focal lengths, adding a 50mm normal focal length to the 28mm one that’s been the common choice for smartphones*.

* Focal lengths given as equivalents, of course. The actual focal lengths are 4 and 6mm respectively, telling in terms of how small the sensors actually are.

I’ve personally found this small addition great as a 28+50mm pairing is probably my favorite one to shoot on system cameras.

The 28mm and 50mm pairing opens up a lot of flexibility. 28mm is a great and versatile wide focal lenght. It can occasionally lack intimacy though, and something longer can feel a little more calm, so having a 50mm lens available at the tap of a button is great.

For most people though the subtle differences between focal lengths probably isn’t enough to really sell them on a camera system like this.

This is where one of the most significant recent shifts in photography comes in.

Camera systems in smartphones are inherently required to be very small. Multi-element lenses, focus system, stabilizer and sensor needs to fit in a space way smaller than even a single lens element in dedicated cameras.

This puts extremely strict limits on their performance by simple rule of physics. So even with the improvements of each individual component the overall output would still be limited and the look of the output dictated by these limitations. However the sharp rise in computing power available in increasingly compact and efficient chipsets has begun to offer ways around that.

Supplanting large lenses and sensors with post processing algorithms makes the current smartphones way more capable than they should be considering the size of the camera.

Multi exposure HDR, distortion correction, tonal mapping, vignette removal, noise reduction, sharpening – huge amounts of post processing is done every time you press the shutter on your smartphone. This gets around a lot of the limitations stemming from the tiny size of the sensor and constrained lens designs.

These aren’t new techniques of course, but in the past it took at least a bit of know how and often time in front of a computer to use many of them. Now they’re applied completely seamlessly, automatically and at an instant. Still, this has been the case for a number of years by now.

With the multi camera systems as the one in the X though, things are taken further still. Using the two offset lenses the phone can now determine depth in the images captured. And from the depth map created some interesting post processing trickery can be achieved. Things much more apparent and appealing for the general public than the minute differences between focal lengths.

Portrait mode has been the clearest headline feature for the dual camera system iPhones so far. And for good reason – in general it does quite well to emulate the large aperture/shallow depth of field look of large sensor cameras. It’s certainly not perfect, but when it works the end result is often quite appealing.

With the introduction of the X comes another advance – Portrait Lighting, a feature enabled by the increasing level of processing power in the recent lineup that simulates intricate lighting setups. I’m not sold on the effects myself, but it’s certainly impressive from a technical standpoint.

My kid's first bike and common lilacs. Two shots made using "portrait mode". And while the mode obviously works well for people photos I really like it for other things too.

So with these features more and more limitations of the small camera systems are circumvented. Surprisingly little of this approach has been seen in dedicated cameras so far, but it’s easy to imagine this as the future for at least a lot of the day to day photography that most people do.

Gear heads will probably quibble about things the authenticity of the images or the believability of the bokeh, but for most people the convenience of having a small system with appealing output will trump any such reservations. And I wouldn’t be surprised if computational photography ends up changing our perception and relationship to photography as a whole.

Still, already in the here and now there’s quite a bit to like with the output of contemporary smartphones. Even for the discerning. You’re generally getting output that’s on par or ahead of what most dedicated compact cameras could muster just a few years back.

Especially if you’re willing to jump through a few hoops to squeeze the best out of the smartphone cameras.

These last few weeks have been busy. Going to the ocean offers a small respite. We grab a snack on the jetty, examining bird and fish.

Third party apps & raw capture

With the post processing pipeline becoming such an integral part of the look of the output it’s probably not a surprise that different pieces of software can have a significant impact on the resulting images. Some apps are tailored to achive the absolute best image quality possible, others simply focus on offering additional ways to influence the resulting images.

Raw capture

If you strive to get the best image quality possible out of the smartphone camera then enabling raw capture is a must. It offers more detail, increased flexibility for editing and smoother tonality compared to the default, compressed output*.

*Both tone mapping and noise reduction in iOS is unsurprisingly heavy handed. Highlights blow out often, which I’ve found frustrating for a while (an issue that feels like it’s been more frequent in recent software versions, though I’ve got no way to back this up). Shooting beyond ISO 20 (no, that’s not missing any zeroes) makes any semblance of detail into unrecognizable smear by noise reduction. Overall I’m not a big fan of the default output.

There are a few caveats with shooting raw though. File sizes are significantly larger (usually around three times the size). Some editing apps also have a hard time accessing the full data in the raw files, instead falling back to the super low quality preview which then gives far lower quality than simply using normal JPG/HEIF files. And even with editing apps that support raw files you’re not quite getting output on par with what you can get from dedicated software on a computer. In this regard I’ve approached the workflow more as I would’ve with a dedicated camera – with images taking a roundtrip through Lightroom for culling and editing. In some ways more cumbersome than editing on the go on the phone, but I think it’s actually faster and more efficient in the end, in addition to getting the highest possible output quality.

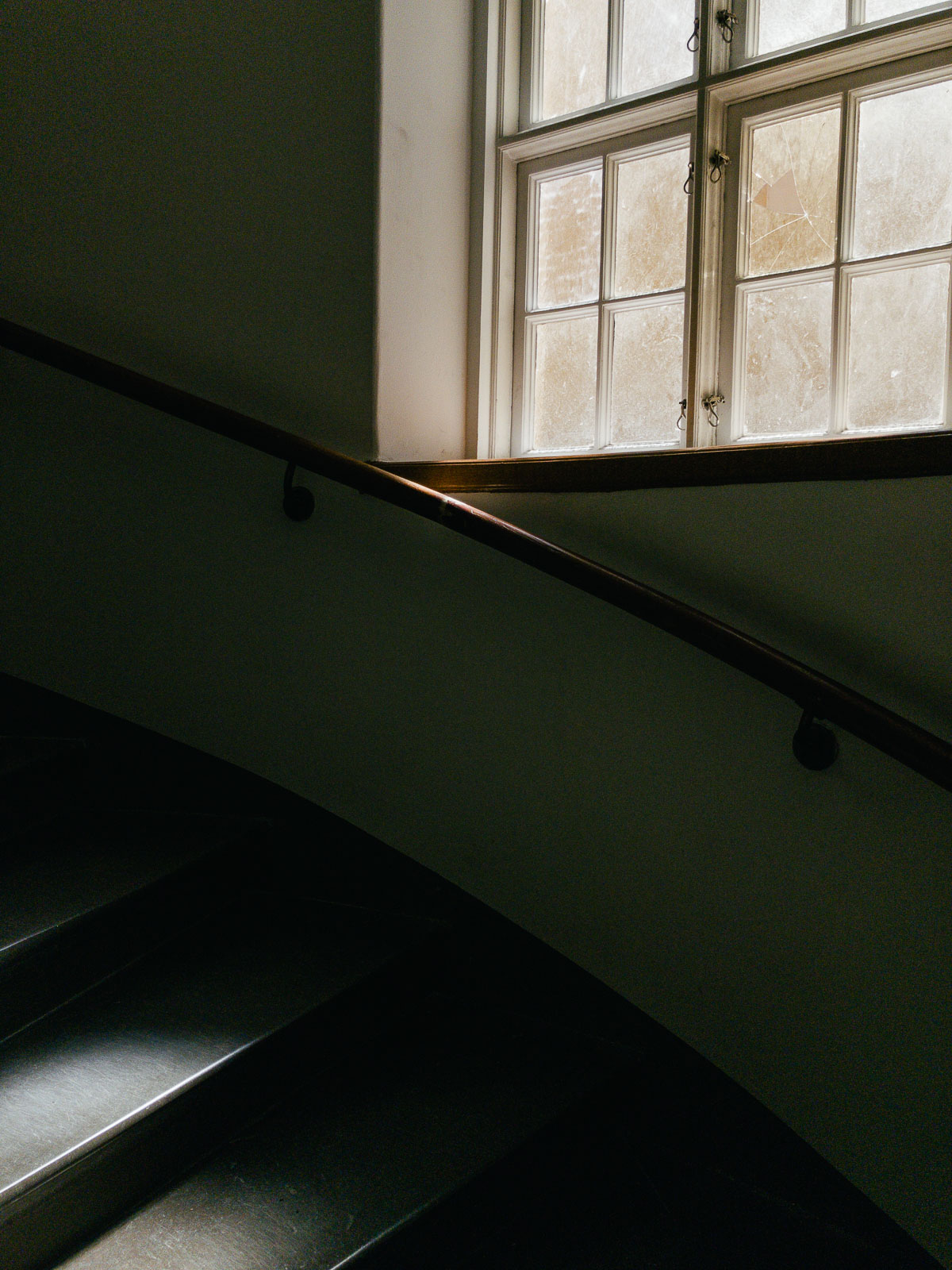

A quick comparison between compressed jpg output (1) and raw (2). Note for instance the harsh looking window frames and lack of subtle detail in smooth areas due to aggressive noise reduction in the jpg.

The final thing to be aware of is that only third party apps offer raw.

In and off itself this poses a few minor niggles. You can’t launch third party cameras from the lock screen which is probably the biggest practical hurdle. Most of the apps are also paid which can be a little annoying if you happen to purchase an app (or two, or three) that doesn’t at all suit you. I’ve been through quite a few myself and always ended up going back to the default app in the end. However I’ve recently found an app that I very much enjoy.

Raw capture gives a lot more leeway for edits big and small. It’s possible to work with far subtler tonalities than with the default output.

Halide

Halide is a third party camera app that’s very thoughtfully put together. The designer of the app – Sebastian de With – has been at Apple in the past and is a photographer himself, something that becomes very apparent with how practical and well considered every feature is. Everything from basic interactions, typeface choices, gestures and haptics is exceptionally well designed.

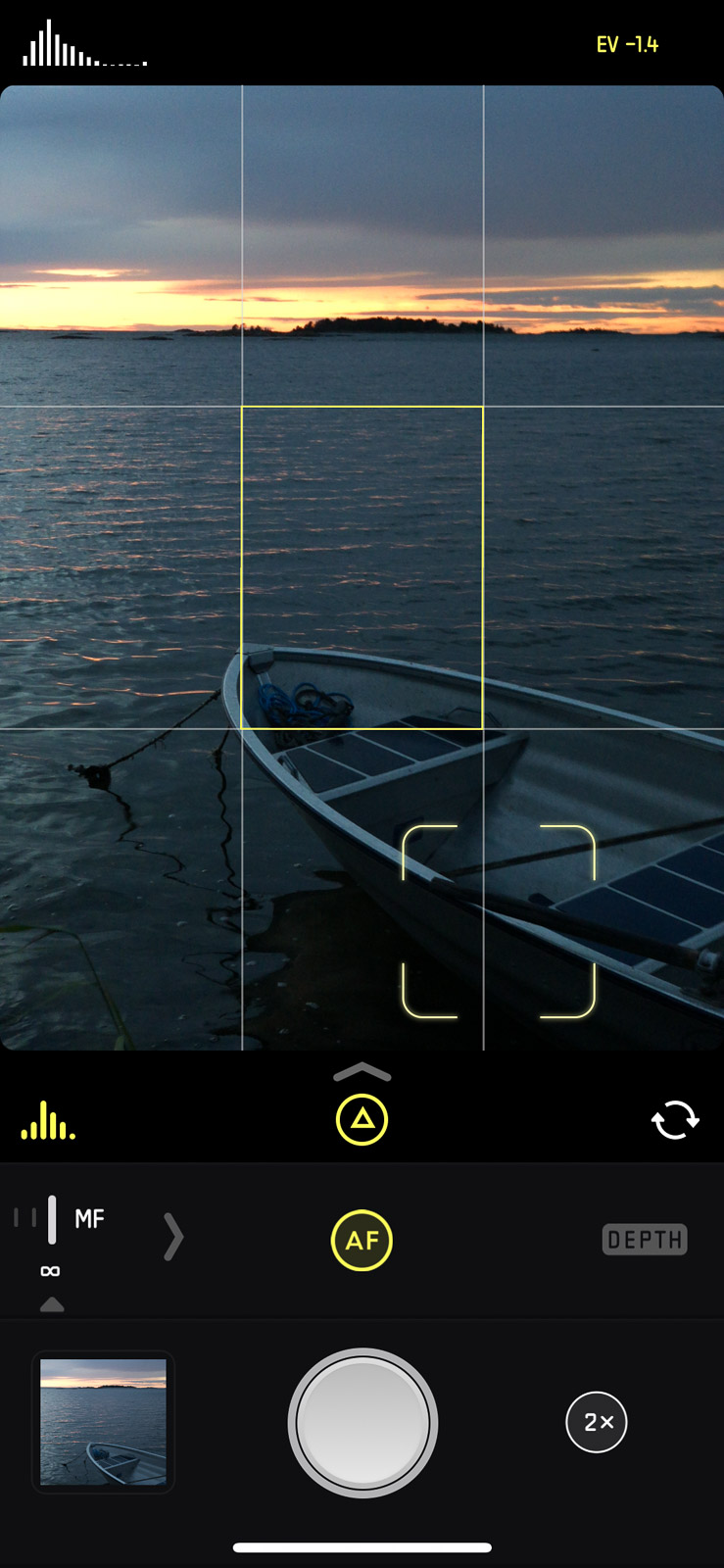

It’s pretty much a stand in for the default camera app with a bunch of neat tricks that makes it a little easier to really get the most out of the iPhone cameras. Beyond offering raw output some of my favorite features include a live histogram, instant exposure compensation by swiping anywhere and a wonderful little haptic feedback when you’re level.

Overall it’s by far the most pleasant to use third party camera app I’ve tried and around half the photos in this post were captured using the app.

Halide has a few features that makes it very pleasant to use and makes it easier to get usable photos even under surprisingly challenging conditions.

Influencing portrait mode with Focos

Another interesting example of what’s possible by changing the post processing pipeline is the app Focos. It’s centered around portrait mode with a lot of features for influencing the look of the output. It’s a fun app to play around with. If nothing else than for the futuristic feel of refocusing an image long after capture.

It’s easy to get carried away when playing around with all the settings in the app, but with balanced edits the output can look very pleasing and get away a little bit from the overly well corrected look of the default portrait mode (though the issues with the depth maps being less than perfect at times of course carries over).

You can really go overboard with the settings in Focos, resulting in very artificial looking images highlighting the limitations of the depth maps generated. Still with the right image and more subtle processing the output can look very pleasing.

It’s pretty fascinating to have the focal plane, depth of field and character of bokeh as post processing options. It’s not wholly uncommon for me to take the same shot at a few different aperture settings when shooting a dedicated camera, if I’m unsure if a prefer a shallow or deep depth of field. But when changed as simply as white balance or contrast there’s no longer any need for that. You’re free to consider other aspects at time of capture instead and can find the ideal balance between isolation and context with just a few taps and swipes.

We’ve been going here since she was just months old. As she grew new activities and obstacles were discovered. The imposing tower the only thing still unconquered. For the longest time it seemed impossible. Then suddenly she scaled it like there was nothing to it.

The little slate came out of my pocket and captured the moment, all before she realized that now she also needed to figure out how to get down.

In use

The last thing I want to touch on is simple haptics and operation of the phone as a camera.

Once you start shooting it more considered, not only for occasional snapshots, it’s something of a mixed bag. If you’re looking to emulate the process of using a dedicated camera the experience will fall short. But if you embrace the process there are some clear pros in addition to the cons.

The grumpy part in me want to moan about the lack of dedicated controls, that there’s no eye level viewfinder and how slippery the phone is to hold steady. But with a mindset like this you risk not recognizing advantages in new approaches. So I’ve tried to keep an open mind towards the shooting experience the phone offers. Shooting and treating it more like a proper camera has revealed both expected and unexpected facets.

Overall I’ve enjoyed it more than expected. Few of the drawbacks ends up real showstoppers and can mostly be worked around.

The screen is very good* so there’s not a huge need for a finder. It’s trivial to get very exact compositions and get good exposure. Shooting Halide also gets around most of my niggles with the default camera. Finding a good grip and bracing the phone properly also let’s you shoot at really slow speeds thanks to the built in stabilizer.

*It’s really a bit silly how far ahead the screen is compared to even higher end dedicated cameras. Resolution, color reproduction and brightness are all way better on the phone.

Autofocus, shot to shot time, shutter lag and blackout are generally all pretty good too, though there can be some occasional stutters.

I’ve also touched on how nice it is to have two focal lengths available at the touch of a button, but it’s worth underscoring just how great I’ve found this. The addition of the 50mm camera might actually be the change that has the biggest impact for my own use. As it turns out the type of images I enjoy making with the phone (and where I find it’s imaging characteristics work best) often look better with the perspective* a 50 offers rather than what you get from a 28. And from the images in this article about two thirds are made using the 50 vs the 28. I’ve even ended up occasionally wishing I could change lenses on my dedicated camera as quickly.

*Yes, I know perspective is an effect of distance rather than focal length, but let’s keep things simple for now.

The phone is also incredibly discrete. No one bats an eye at someone making smartphone snaps but a dedicated camera is certainly noticed more by the people around you.

The biggest appeal though is how the phone is practically always close at hand. I always have the phone with me, usually in my pocket. So at any given time it’s unlikely that I’m more than a few seconds from capturing something with my phone.

The phone being at hand makes it trivial to capture fleeting moments, regardless of if it’s a kid chasing crocodiles or a little kitchen renovation vignette.

With a dedicated camera it’s not uncommon to have it laying around somewhere else in the house, in a camera bag or you might’ve even left home without it. So unless you’re actively shooting the smartphone is probably quicker to get out and grab a shot a good deal of the time.

Proper pocket cameras can of course offer that very same convenience and I’ve been through a few. But as they also come with their own sets of trade offs in terms of controls, haptics or image quality I’m actually not as convinced by them that I used to be*. Besides the phone is even thinner and easier to fit in pockets than pretty much any dedicated camera past or present. And compared to how I’ve previously felt about the smartphone as a camera, this is actually a pretty significant shift in perspective.

* I touched on this quite a bit in my recent review of the Olympus mju II.

That’s not to say there aren’t ways I prefer dedicated cameras though. I still feel a lot more engaged with the process having the camera to my eye, changing settings through hardware input and triggering the shutter with a well weighted button. The methodical approach of shooting film in particular makes me stay more in tune with the moment I’m in and the images I’m making. Compared to that shooting with a phone makes me feel skittish.

And while image quality can sometimes come close to the output of a dedicated camera there are still nuances to the output that often makes the phone images look less appealing, even at smaller sizes. And as you move to larger magnifications the gap to really good dedicated cameras often becomes increasingly noticeable.

Still it usually takes a trained eye to spot the difference. Besides that I’ve also made a few true keepers of fleeting moments that I’m not sure would’ve turned out on my usual cameras, had I even managed to capture them in time.

It was the hottest summer anyone remembers. Going for a swim became a daily routine. Despite the end of the season drawing close it was hard to imagine anything else.

Bottom line

What makes a camera great? Is it image quality? Keeper rate? Consistency? Ease of use? Or is it defined by the images you actually end up making with it?

I’ve got to say that shooting the iPhone X half way seriously for the past few months have made me question some things in my general approach and reconsider others.

If it’s possible to capture images and moments as the ones just above with this phone, is it really worthwhile to spend my time fuzzing with film? Do I really need to shoot anything else than this? Am I getting images that are better or worse in the long run?

There’s rarely a binary answer to questions like these. Beyond simple documentation I also shoot for fun. And at the moment I find it more fun to shoot with dedicated cameras. Film ones in particular, though digital is fine too.

In theory I could probably do a lot of my day to day documentation shots on my phone and be mostly fine with the output. Leaving the dedicated camera for times when I’m shooting in a dedicated fashion.

In practice though the smartphone lacks a sense of connection with it as a tool. I also miss that last bit of presence in terms of image quality and rendering. And from experience I’m at the happiest with my shooting when I’m sticking to one single camera for all or at least most of the shooting I do. And as it’s a few very clear steps ahead in both enjoyment and image quality for now that will probably remain a film Leica.

That’s not to say that things are unchanged however. Because while a smartphone has some ways to go to replace my main cameras I feel less and less of a need to carry a dedicated pocket camera. Something I certainly didn’t expect would happen anytime soon. And who knows how I’ll feel with another few years worth of iterations on the smartphone cameras.

So while I’m not eager to jump on the bandwagon of proclaiming the smartphone camera as something unreservedly brilliant, I’m finding it has more of a place in my photography than it used to.

Return Home

All photos in this post were taken using the iPhone X. The image of the phone itself was made using the Fuji X100T. Exif-data is intact. Open any image in a new window for a closer look.